A trio of codebreakers has discovered and deciphered a treasure trove of misplaced letters written by Mary, Queen of Scots.

The 57 secret letters, from Mary Stuart to the French ambassador to England between 1578 and 1584, had been written in an elaborate code.

The findings come 436 years after Mary’s demise by execution on February 8, 1587.

Most of the letters had been saved within the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, primarily in a big set of unmarked paperwork that had been additionally written in cipher — particular graphical symbols.

The paperwork had been listed as courting from the primary half of the sixteenth century and considered associated to Italy.

Then, a trio captivated with cracking historic ciphers stumbled upon the paperwork.

George Lasry, a pc scientist and cryptographer from France; Norbert Biermann, a pianist and music professor from Germany; and Satoshi Tomokiyo, a physicist and patents professional from Japan, all labored collectively to seek out the reality behind the paperwork.

The multidisciplinary group has labored collectively for 10 years to seek out and perceive historic ciphers.

Lasry can also be a member of the DECRYPT Project, which digitises, transcribes and identifies the that means of historic ciphers.

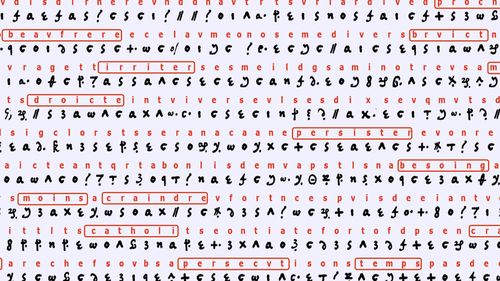

Once the researchers started working by the distinctive ciphers, they rapidly realised the correspondence was written utilizing French, and there was nothing Italian about it.

The group spied verbs and adverbs that used a female kind, mentions of captivity — and a key phrase: Walsingham.

Sir Francis Walsingham was Queen Elizabeth I’s secretary and spymaster.

Together, all indicators pointed to the truth that the group could have discovered letters of Mary Stuart thought misplaced for hundreds of years.

The outcomes had been revealed Tuesday within the journal Cryptologia.

“Mary, Queen of Scots, has left an extensive corpus of letters held in various archives,” Lasry stated in an announcement.

“There was prior evidence, however, that other letters from Mary Stuart were missing from those collections, such as those referenced in other sources but not found elsewhere.

“The letters we have now deciphered are most certainly a part of this misplaced secret correspondence.”

The newly deciphered material, which is about 50,000 words total, sheds new light on Mary’s time spent in captivity in England.

Mary Stuart, a Catholic, was first in line for the succession to the English throne after her Protestant cousin, Queen Elizabeth I.

Catholics considered Mary as the rightful, legitimate sovereign.

She was executed by decapitation at the age of 44 for her alleged part in a plot to have Elizabeth I murdered.

But Mary wasn’t idle in captivity.

She maintained regular correspondence with allies and tried to recruit messengers to hide her letters from enemies.

The new letters reveal new details about her communication with Michel de Castelnau, sieur de la Mauvissière, the French ambassador to England.

The correspondence may have started as early as 1578.

The ambassador forwarded letters from Mary to her agents in France.

The English government was aware of her confidential activities, and in turn, Walsingham spied on Mary during her captivity.

He was able to snag some of her letters through a spy inside the French embassy — which is why some of the 57 letters deciphered by the team can also be found in British archives.

In the letters, Mary complained about the conditions of her captivity and her poor health.

She lamented that her negotiations with Elizabeth I to be released weren’t carried out in good faith.

Mary detailed her dislike of Walsingham as well as Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester — a favourite of her cousin.

Mary also tried to bribe the queen’s officials.

The letters also showcase the distress Mary felt when in August 1582 her son, James — the man who would eventually become King James I of England two decades later — was abducted.

Dr John Guy, a fellow in history at Clare College in Cambridge, England, and author of Queen Of Scots: The True Life of Mary Stuart, was able to read the study ahead of its release.

“It’s a shocking piece of analysis, and these discoveries will probably be a literary and historic sensation,” Guy said.

“They mark an important new discover on Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, for 100 years.”

The letters show that even in captivity, Mary was “a shrewd and attentive analyst of worldwide affairs” who was involved in the political affairs of Scotland, England and France, Guy said.

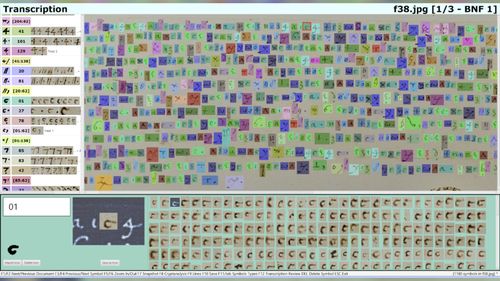

The research team used complex methods combining computer algorithms, linguistic analysis and manual codebreaking techniques to decipher the letters.

“Breaking the code was not a eureka second — it took fairly some time, every time peeling one other layer of the ‘onion,'” Lasry said.

Initially, the researchers could only read 30 per cent of the text using the computer algorithm.

Then, they manually analysed the symbols and tested their meanings through trial and error using contextual analysis.

“This is like fixing a really massive crossword puzzle,” Lasry said.

“Most of the trouble was spent on transcribing the ciphered letters (150,000 symbols in complete), and decoding them — 50,000 phrases, sufficient to fill a e-book.”

Amateur detectorist finds gold necklace linked to Henry VIII

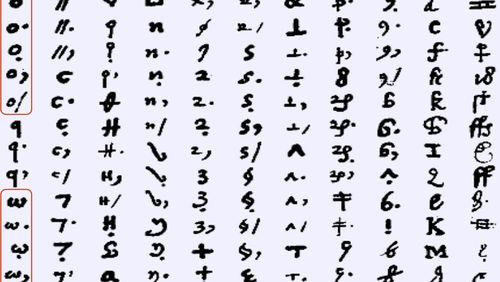

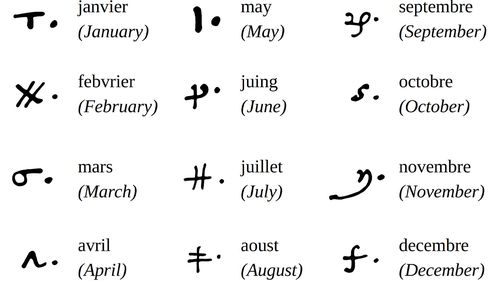

The ciphers were homophonic, meaning each letter of the alphabet could be encoded using several cipher symbols, according to the researchers.

This practice ensured that certain symbols weren’t used too frequently.

The text also included dedicated symbols to signify common places, words and names.

The team was also able to compare the letters with some documents included in Walsingham’s papers in the British Library in London and trace similar ciphers.

“We have cracked tougher codes, and we have now deciphered an occasional letter from a king or queen, however nothing in comparison with 50 new letters from some of the well-known historic figures,” Lasry said.

It’s likely that other coded letters from Mary are still missing.

In the meantime, the letters provide a wealth of information for researchers to dig into.

“In our paper, we solely present an preliminary interpretation and summaries of the letters,” Lasry said.

“A deeper evaluation by historians might lead to a greater understanding of Mary’s years in captivity.

“It would also be great, potentially, to work with historians to produce an edited book of her letters deciphered, annotated, and translated.”

Source: www.9news.com.au