It all began for 61-year-old mum Paula* again in September when she started wanting into authorities funding bonds on-line.

“With the cost of living going up, I was thinking anything I can do to earn a little bit of extra money will help,” she stated.

Government bonds are a means for buyers to lend cash to the federal government, normally at a barely increased rate of interest than a time period deposit at a financial institution would supply.

The curiosity is paid at common intervals till the bonds attain their maturity date and the preliminary funding is returned.

Eager to get began, Paula did a search on-line and clicked on a hyperlink for what seemed to be a Commonwealth Bank commercial promoting authorities Treasury bonds.

Paula stuffed out an enquiry type along with her particulars and waited for somebody to get again to her with extra data.

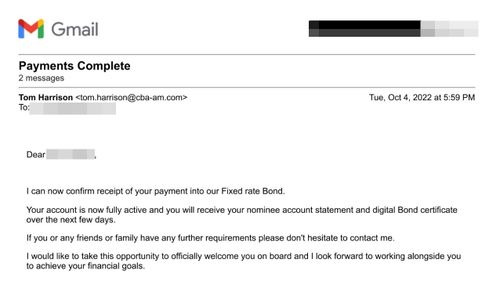

Not lengthy after, a person claiming to be a Commonwealth Bank account supervisor phoned Paula.

“He said, ‘My name is Tom Harrison, I’m from the Commonwealth Bank and this call is being recorded,'” Paula stated.

“He sounded very convincing and official.

“Straight away, I believed him – and that is what acquired me into bother. I went together with it and it became a nightmare.”

At Paula’s request, the man sent her some more information about the government bonds via email.

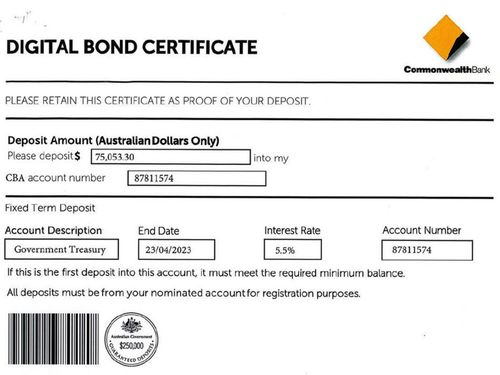

All of the documents had prominent Commonwealth Bank branding.

The interest rate being offered was 5.5 per cent, which was a per cent or two higher than what Paula had seen offered elsewhere.

Paula decided to use $75,000 of her savings – which she had sitting in a Qudos Bank account – to buy the bonds.

She said she initially transferred $1000 to the account the man nominated as a way to test she had the right account number.

“It went by way of however then the person stated to me, ‘I’ll must refund you that $1000 as a result of the method is we now have to do (the buying) in bulk,'” Paula said.

“I believe this was a technique to make me belief him extra, and it labored, as a result of what sort of scammer would refund cash?”

Paula then transferred the $75,000 over three instalments and was sent a digital certificate confirming her purchase.

It wasn’t until a week later, when Paula happened to see an email from Macquarie Bank warning customers about government bond scams, that she began to suspect something was wrong.

“This is what triggered all the pieces, I used to be pondering, ‘Oh no’,” she said.

Paula said she tried to call “Tom Harrison” but could not get through to him, so she went straight to the Commonwealth Bank, where a teller confirmed it was a scam.

“It was simply horrible,” she said.

Looking back, Paula said there were red flags she couldn’t believe she missed, such as the scammer’s email coming from a slightly different address to the one used by Commonwealth Bank employees.

“I do know it is my fault. When I appeared on the paperwork, it appeared real to me on the time, however now I can see the fakeness in it.”

A spokesperson for the Commonwealth Bank also confirmed the bank does not directly sell government bonds listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX).

Instead, government bonds are sold through the bank’s online stockbroking subsidiary, CommSec.

“We’re conscious of subtle bond scams that faux to be CBA, or different organisations, and we commonly work with business companions to fight them,” the bank’s spokesperson said.

“If somebody thinks they’ve been scammed then they need to contact their financial institution instantly.”

A spokesperson for Qudos Bank said it was investigating Paula’s case and could not comment on the matter.

Red flags aside, Paula is among an increasing number of Australians who have fallen victim to sophisticated investment bond scams.

According to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) Scamwatch, Aussies have lost $33.8 million so far this year to imposter investment bond scams.

This is greater than double the losses for the entire of 2021.

Scamwatch received over 400 reports of imposter bond scams between January 1 and November 20 this year, but the real figure is likely to be much higher, with research showing only around 13 per cent of scam victims report their losses.

Earlier this year, ACCC Deputy Chair Delia Rickard described the increase in bond investment scams as “alarming”.

“As rates of interest rise, folks trying to spend money on bonds are falling sufferer to those scams after looking on-line for funding alternatives. This is commonly after they full enquiry varieties on faux third-party comparability web sites,” Rickard said.

“These comparability websites can seem very convincing, and persons are offering their particulars underneath the impression that these are legit Australian websites evaluating actual monetary companies.

“Convinced they are making a long-term, legitimate investment, it’s common for victims to deposit larger sums upfront and not check their account for months before realising they were scammed.”

As many victims had been contacted by cellphone, Rickard stated a key solution to forestall being scammed was to name a financial institution or monetary service instantly utilizing particulars sourced your self – quite than utilizing any cellphone numbers or hyperlinks offered.

Banks additionally had an vital function to play in stopping scams, Rickard stated.

“Organisations should actively monitor for, warn about and promptly seek the removal of websites impersonating their brand,” Rickard stated.

*Name has been modified.