Frank W. Abagnale Jr. was irritated.

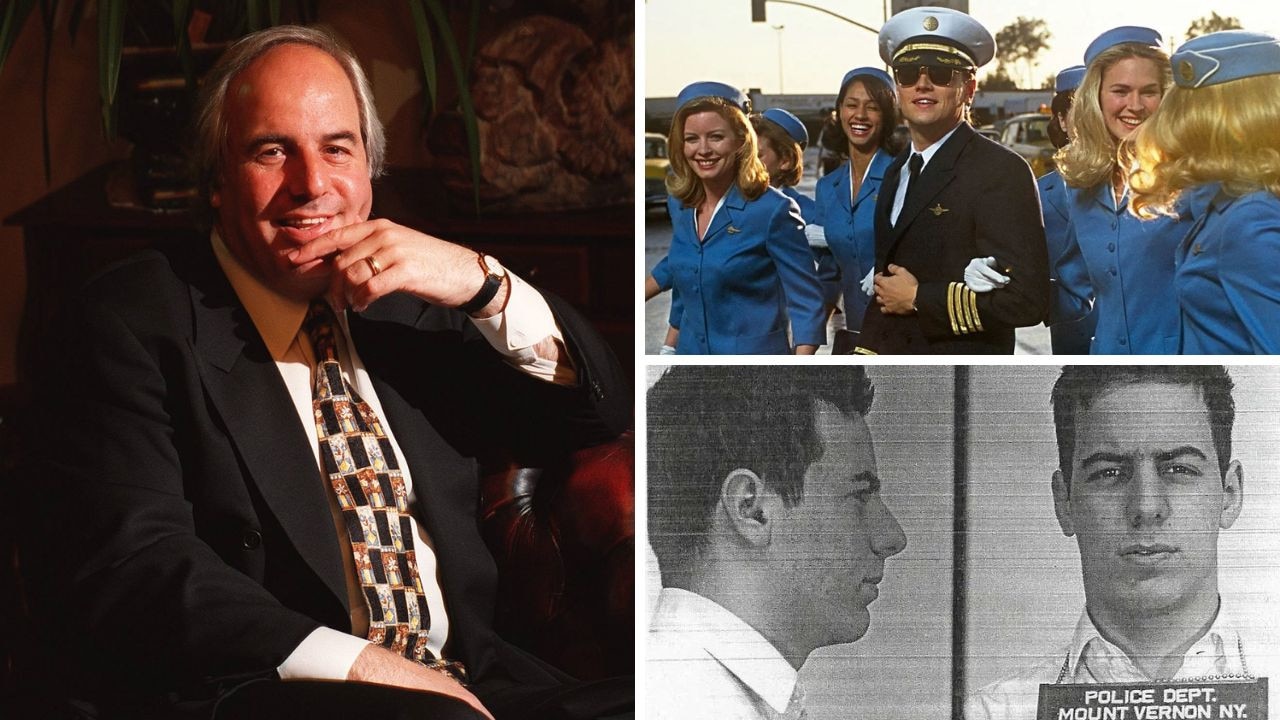

The Times of London had reviewed my 2019 e-book about serial liars, Duped, and a photograph of Leonardo DiCaprio in full pilot regalia accompanied the piece.

It was the well-known nonetheless from Catch Me if You Can, Steven Spielberg’s 2002 movie impressed by Abagnale’s best-selling memoir from 1980.

Via electronic mail, the “reformed” con artist and writer — who now advises companies, banks, malls and the FBI on fraud prevention and cybercrime — needed me to know that it bothered him that “everyday someone writes an article about a bank robbery, forgery, con artist, or even cybercrime and they refer to me.

“The crime I committed was writing bad checks,” he wrote. “I was 16 years old at the time. I served five years total in prisons in Europe and the US Federal prison system. In 1974, after serving 4 years in federal prison, the government took me out of prison to work for the FBI. I have done so now for more than 43 years.”

He added that he had repaid all of his money owed.

His misery shocked me.

Abagnale by no means appeared embarrassed by his previous — not on To Tell the Truth nor The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson nor in high-paying talking gigs across the nation.

His grifter-made-good story was an enormous promoting level.

According to each Abagnale himself and his autobiography, within the mid-Sixties and early ’70s, when he was between 16 and 21, he had impersonated a Pan Am pilot, flying some 3,000,000 miles to 82 international locations totally free.

He claimed to have posed as a health care provider in Marietta, Georgia, a sociology professor at Utah’s Brigham Young University, and a lawyer within the lawyer normal’s workplace in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

During that interval, he allegedly cashed 17,000 bogus checks totalling $2.5 million {dollars}, with the FBI in sizzling pursuit.

That’s the legend, anyway — as informed in print, movie, theatre and speeches worldwide. It’s a narrative that has introduced Abagnale fame, fortune, and most of all, legitimacy.

So why did he object to being in a e-book about deception?

I requested Abagnale — who based Abagnale & Associates, a agency that advises corporations on fraud prevention, in 1976 — this query in my reply electronic mail, however he by no means responded.

And I put it out of my head till June 2020, when one other electronic mail popped up in my in-box, this time from a person named Jim Keith.

In 1981, Keith, then supervisor of safety at a JC Penney in St. Louis, heard Abagnale communicate at an space highschool about turning his life round.

Keith and a neighborhood detective had been within the viewers. Much of the speech was stuffed with “technical information regarding bad checks” and it was, to Keith, incorrect.

“We walked away with a sick feeling that we and those students were sold a bill of worthless goods,” Keith stated.

Infuriated, he started researching Abagnale.

Keith was, his daughter, Heather Crosby, informed the Post, “Like a dog with a bone … He was determined to show this guy was a fraud.”

Accusations that Abagnale had fabricated his life story had been swirling for a number of years, starting with the San Francisco Chronicle in 1978 and the Daily Oklahoman quickly after.

But with no family web, these tales by no means reached vital mass. Abagnale’s fantastical feats remained unchallenged.

Keith finally teamed up with a professor named William Toney, a former border patrol officer and professor of felony justice at Stephen Austin University in Nagodoches, Texas.

He, too, had witnessed an Abagnale speak and didn’t purchase it. So he enlisted his college students to assist examine.

Keith despatched me an 87-page file of previous newspaper clippings, courtroom paperwork, letters — from airways, college officers, authorities sources and others — together with correspondence from Toney, who died in 2010.

Some of what Abagnale stated was true.

He did forge checks, masquerade as pilots, sit in a number of soar seats, escape a jailhouse and go to jail in Europe.

But the remainder of his not-so-humble brags had been “inaccurate, misleading, exaggerated or totally false,” claimed Keith, who died in 2021 at 77.

As Abagnale’s former talking agent, Mark Zinder, 66, informed the Post, “He was a two-bit criminal. I’m embarrassed that I ever associated with the man.”

Abagnale by no means pretended to be a professor at Brigham Young or a doctor in Georgia. He by no means posed as a lawyer within the Baton Rouge lawyer normal’s workplace.

He was by no means a advisor to the US Senate Judiciary Committee.

Chief counsel Vinton D. Lides informed Keith that an “initial check of employment records for the last ten years, does not indicate that one Frank W. Abagnale, Jr. has ever been employed as a consultant, or in any other capacity, by this Committee.”

(Although Abagnale has claimed to have used the aliases Frank Williams, Frank Adams, Robert Conrad, and Robert Monjo, there’s no proof he did.)

Nor did Abagnale steal cash from a deposit drop at Boston’s Logan Airport whereas dressed as a safety guard, as he’d claimed in his memoir and talks.

And his Pan Am antics had been severely embellished.

“I am sorry not to have the time or the inclination to rebut the same dribble this individual has been peddling for years,” Andrew Okay. Bentley, Pan Am’s director of safety, wrote Keith on Mary 18, 1982.

It’s additionally unimaginable for Abagnale to have accomplished his felony enterprises between ages 16 and 21: He spent a lot of these years behind bars.

That’s additionally why he might by no means have cashed 17,000 fraudulent checks value $2.5 million, stated Alan C. Logan, writer of “The Greatest Hoax On Earth,” about Abagnale. “The time he wasn’t in some prison or jail amounts to about 14 months. Cashing 17,000 checks in that period is 40 checks per day.”

In November 1970, the 21-year-old was picked up in Cobb County, Georgia, after cashing 10 faux checks value a grand whole of …$1,448.60. He was despatched to a federal penitentiary in Petersburg, Virginia, in April 1971 and sentenced to 12 years.

Abagnale has claimed that the federal government sprung him from Petersburg to work with the FBI, however “There is no evidence to support this claim,” stated Logan. The FBI wouldn’t remark.

While an FBI agent was searching for him, there may be additionally no proof that the bureau arrange a process pressure devoted to his seize.

In reality, Abagnale was arrested once more, in 1974, for stealing artwork and pictures gear from a Texas summer season camp the place he was working. He was 26.

In 1982, Toney introduced his findings on Abagnale on the International Platform Association, a audio system’ conference in Washington, DC. Others on the schedule included Carl Sagan, David Brinkley, F. Lee Bailey — and Frank Abagnale, Jr.

But after getting wind of Toney’s speak, “How to Catch a Con Man,” Abagnale by no means confirmed up.

According to information obtained by The Post, Abagnale threatened to sue Toney for libel and slander; Toney filed swimsuit towards Abagnale for “damages”.

They settled out of courtroom in 1985.

As for Abagnale’s justification in his memoir and in speeches that he solely robbed massive firms, that’s news to Paula Parks Campbell, a former flight attendant who met him — carrying his TWA pilot uniform — on a airplane from New York to Miami in 1969.

“TWA was the giant,” says Campbell, 75, who lives outdoors Baton Rouge.

Abagnale despatched two dozen pink roses and a 5-pound field of chocolate to her lodge. When she landed in New Orleans the next day, he was there on the airport.

“He was very charming, but he smelled bad,” Campbell informed The Post. “It wasn’t body odour. It was fear.”

When he shocked her at 4 different airports, she started to get uneasy however determined to have him meet her mother and father in Baton Rouge.

“My parents and brother fell in love with him,” she stated.

After dinner, her mom invited Abagnale to return and she or he’d train him to fish. But on the experience again to New Orleans, Campbell informed him she didn’t wish to see him anymore.

A couple of days later, nonetheless, Abagnale popped up at her mother and father’ door unannounced, telling them he was on furlough from TWA.

They invited him to remain over — it ended up being six weeks.

Her mother and father, a nurse and trainer, handled Abagnale like one in all their youngsters.

He thanked them by rifling by way of her mother and father’ checkbooks and stepping into the financial savings accounts of her brother and a household pal, stealing about $1200 from them.

“He said he never hurt little people, just went after big businesses,” stated Campbell. “That’s the one that sticks in my craw. My mama’s heart was broken.”

Soon after, Abagnale despatched a mea culpa to the household.

“There are no words to express how ashamed and sorry I am,” he wrote. “You people have showed me more love in six weeks than I have ever seen in my lifetime. Even though I will go to prison, every cent I owe you will be repaid.”

Campbell, whose mother and father are lengthy gone, continues to be ready.

So is Mark Zinder, who sued Abagnale for breach of contract and misplaced fee for

speeches Abagnale by no means gave, and stated he’s nonetheless owed $15,000.

And Nelda McQuarry, who stated she invested $20,000 with Abagnale in what turned out to be a real-estate rip-off.

Abagnale moved from Houston to Tulsa in 1985, alongside along with his spouse, Kelly Welbes Abagnale.

In 1991, the couple, who had three sons, filed for Chapter 7 chapter, claiming to have $308.752 in belongings and $1.6 million in debt. (They now dwell in Daniel’s Island, South Carolina, and are apparently now not in chapter.)

There are indicators that the ruse is perhaps slowing down.

Abagnale was appointed a “Fraud Watch Ambassador” for AARP in 2015, educating shoppers on rip-off prevention.

He co-hosted AARP’s podcast “The Perfect Scam” from 2018 till at the least 2022.

But, in response to an organization spokesperson, Abagnale is “no longer associated with AARP.” A July 2022 article on the corporate’s website online notes that “many of his tales have since been debunked”.

Google added a disclaimer to a 2017 Abagnale speak that has garnered 15 million views, noting that it “does not lay claim to the validity of the actions described therein.”

Abagnale doesn’t like to speak about his previous, particularly to not journalists (by way of a rep, he declined to remark).

When “Catch Me If You Can” got here out in 2002, he issued an announcement concerning the e-book and movie.

The writer, the late Stan Redding, “overdramatised and exaggerated some of the story … He always reminded me that he was just telling a story and not writing my biography,” Abagnale wrote.

(On the Penguin Random House web site, the e-book is featured within the biography and memoir class.)

In March 2022, Abagnale shocked college students at a Ringgold, Georgia, highschool for a efficiency of the stage adaptation of the film. He reiterated that, “Everything I did I did between the age of 16 and 21. I was caught when I was 21.”

That identical month, Javier Leiva, host of The Pretend podcast, which devoted eight episodes to Abagnale’s fake shenanigans, attended a speech Abagnale gave in Las Vegas.

Ninety per cent of the lecture was about IT safety/fraud prevention, however “the undertone of his false life-story was palpable,” stated Leiva.

Abagnale walked on stage to John Williams’ theme music for “Catch Me If You Can,” and elaborated on his alleged check-forging scheme.

At the tip of his electronic mail to me, Abagnale requested, “Is 50 years not long enough to receive some redemption for a crime committed when one was a teenager?”

“Everyone has a right to a second chance,” stated Leiva. “Forgiveness is a virtue. But basing your entire career on a lie and continuing to profit from it isn’t redemption — it’s just a different version of the same con.”

This article was initially printed by the New York Post and reproduced with permission

Source: www.news.com.au